Auction Date

September 17, 2020

5:00 pm

ET

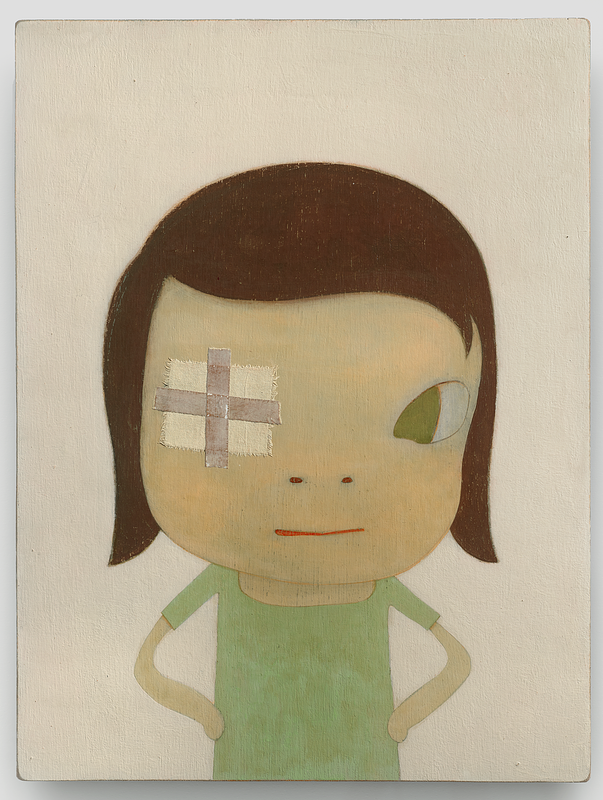

Yoshitomo Nara

Not Yet Titled

Auction Date

September 17, 2020

5:00 pm

ET

Yoshitomo Nara

Not Yet Titled

Estimate:

$800,000 - $1,200,000

Description:

signed in Japanese and dated ‘2011 Nara’ (on the reverse)

acrylic, paper collage and fabric collage on wood panel

17 ¾ x 13 ⅜ in. (45.1 x 34 cm.)

framed: 24 ½ x 20 ⅛ in. (62.2 x 51.1 cm.)

Executed in 2011-2016.

Provenance

Blum & Poe Gallery, Los Angeles

Acquired from the above by the present owner

Loïc's Two Cents

It took us about 25 rounds of color correcting to get the image of this Nara right for the app—and we still aren’t fully satisfied. This is because his paintings, under their seemingly flat rendering and simplified formalism, are in fact complex compositional constructions with many sophisticated tonal variations.

Simplicity is maybe the ultimate hallmark of great art. Achieving it is one of the hardest things for an artist, and yet the simplification of ideas and form has been the lifetime quest (and perhaps defining combat) of countless artists throughout art history—think Malevich, Cézanne, Gauguin, Brancusi, Picasso, Duchamp, Rothko, Pollock, Ryman, Warhol, and so on.

Take Brancusi’s «Bird in Space», incorrectly translated title from French « l’Oiseau Qui Prend Son Envol » (The Bird that is About to Fly Away), it took him 20 years to polish this thought, artistic process, and ultimately the sculpture itself in order to formalize this complex movement into one of the purest, but at the same time most genius sculpture of the 20th century.

Nara has placed himself perfectly within this tradition. His ability to simplify the complex is why it is so easy to mistake the artist as an illustrator of devilish children and fail to notice (or perhaps subconsciously sidestep) what is really happening in each of his paintings. Much like Brancusi, who pared down to the core expression of form and movement, Nara hones in on root-emotions.

His use of toddlers is deliberate, as their emotions (in whatever expression they take) are pure, condensed, and whole. By shielding his characters from the intellectual corruption that comes with age, and steering away from unnecessary formalism and visual depth, Nara creates an amplified milieu, where everything from the most fleeting emotions and layered personality traits are revealed with the utmost poignancy.

Like On Kawara’s date paintings, each of Nara’s paintings, seemingly interchangeable, are in fact every time a unique iteration of radically different mental expressions. The subtle shifts in the tilt and color of the eyes, the undertone in the cheeks (hence the color correcting issues), or the slight variations in the curvature of the mouth are enough to power each painting with a completely new psychological dimension. In this regard, Nara reminds me of Rothko, who pared down his paintings to simple rectangles, which allowed him to charge his works with so much psychological intensity through the use of subtly variating colors that would frazzel even the most blasé high school kid.

Nara’s paintings may seem humorous, but they are no joke. Nara may be playful, but he is dead serious and so is his art.

Catalogue Notes

With his brazenly irreverent paintings of mischievous little children, Yoshitomo Nara has become one of the first Japanese artists to emerge on the scene as a global sensation. His young subjects exist in a transitional space between the innocence of youth and the harsh reality of adulthood. Visually, this push and pull of young and old, innocence and guilt is achieved through an abrupt convergence of punk aesthetics and the Japanese notion of cultural cuteness known as kawaii. Executed in 2011, Not Yet Titled is an exceptional example of Nara’s most iconic subject—the single, solitary child—coupled with a new found maturity within the artist’s practice. With her collaged eye-patch and confident stance, the young girl in Not Yet Titled seems to embody Stephan Trescher’s suggestion that “Nara's roly-poly children balance on the razor's edge: they are cute embodiments of infantilism in their chubby-cheeked plumpness. They are the incarnated cry for baby food and love - but at the same time true individuals who will not be defeated, quiet carriers of hope' (S. Trescher, “A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Dog,” Yoshitomo Nara: Lullaby Supermarket, 2001, p. 15). Indeed, Nara’s art continues to push through overly bombastic rhetoric in favor of works that invite careful introspection infused with humor and unconventional subjects.

And yet, beginning in 2011 Nara’s creative process has slowed down to become more meticulous, meditative and introspective. “In the past I would have an image that I wanted to create,” he explained in 2017, “and I would just do it. I would just get it finished. Now I take my time and work slowly and build up all these layers to find the best way” (Y. Nara, quoted in R. Ayers, “‘I Was Really Unthinking Before:’ Yoshitomo Nara on His Recent Work and His Show at Pace Gallery in New York,” Artnews, April 2017). Additionally, Nara has also attributed the reason for the shift in his artistic practice to the Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami in 2011. “I have become more serious after the earthquake,” the artist has stated. “In the past, I created things out of fun. Sometimes they are based on a momentary emotion such as sadness. Now I want to think about how to overcome the sadness with something powerful” (Y. Nara quoted in “Japanese artist has a taste for Hong Kong,” South China Morning Post, March 2015).

Indeed, this new maturity also comes with the emotional and physical maturation of the artist. Whilst there might be many reasons for the young heroin in Nara’s intimate painting to have received the blinding badge of honor over her eye, for the artist the eye patches that have appeared in his later work may be a symbol of his own loss of perfect sight. “My physical power and ability have decayed, of course,” Nara has explained, “but I've obtained new, far-sighted eyes in exchange. Aging does my work good in this sense. I see a big picture, instead of the details I used to focus on with my younger eyes. I enjoy the bird's-eye view of being an older man.” Continuing this discourse, Nara describes how his lack of perfect vision has, in fact, improved the way he sees his paintings: “Having lost my perfect eyesight—or having gained new sight—I started regarding myself just as one part of my audience. I feel my eyes among the other hundreds looking at me. They say human eyes are the mirror of the soul, and I used to draw them too carelessly. Say, to express the anger, I just drew some triangular eyes. I drew obviously-angry eyes, projected my anger there, and somehow released my pent-up emotions. About ten years ago, however, I became more interested in expressing complex feelings in a more complex way. I began to stop and think, to take a breath before letting everything out. That might be another effect of aging (Y. Nara interview with H. Furukawa, “An interview with Yoshitomo Nara,” Asymptote Journal, November 2013).

Comparables:

Also by the artist:

© 2024 Fair Warning Art, Inc.

.png)